“Do you know your Enneagram number?”

Me: “I’m whichever number thinks the Enneagram is [nonsense].”

I know there are some people (none of whom likely read my blog, or will continue to in any case) who feel the Enneagram saved their life or marriage or whatever and might be hurt by my opinion. In such cases, I recommend assigning me a number and attributing my behavior to that.

Seriously, though, I’m not trying to be hurtful. Just saying what I think.

A while ago a friend who is very excited about the Enneagram and finds my recalcitrance irritating asked me whose recommendation I would trust. My answer: Richard Beck (experimental psychologist, critical thinker, theologically astute).

So naturally, first thing this morning, my wife sent me the link to Beck’s interview on the Typology podcast (https://typologypodcast.com/podcast/2018/05/04/episode38/richardbeck).

Having listened to a number of Typology interviews, I’m not surprised that I found Beck’s the most palatable.

He was initially skeptical about the Enneagram. When the host, Ian Morgan Cron, asks whether Beck has changed his mind, he describes himself as “more open, definitely so.” And the episode as a whole suggests that that moderate endorsement is about the limit of Beck’s appreciation from a critical viewpoint. My starting point was deep skepticism as well, and at this point I can go so far as to say, meh. I’m not against it, but I don’t find it especially compelling.

Furthermore, Beck’s way of thinking through what is at stake overlaps with my own to a great extent. I share Beck’s pragmatism. The mystical is real. It matters what works, and the Enneagram seems to work for a lot of people (whatever that means in any given case). Then again, Joel Osteen and Scientology and Oprahism seem to work for a lot of people too. So, there’s that.

Unlike Beck, my skepticism is not ultimately about empiricism. I’m not an experimental psychologist, nor do I think the scientific methods that underpin psychometrics have a privileged place in judging what is true about human beings. I do value those methods as data points, so to speak, but I don’t consider the Enneagram suspect just because it doesn’t measure up to the Big Five’s way of knowing, etc.

There is, nonetheless, a lot to be said for the nuance of the variability and scaling that the Big Five model, for example, allows. As Beck states, the result of that nuance is precisely not types but unique mixtures. He is optimistic about correlating standard psychometrics with the Enneagram, but “not types” is the key phrase, and it weighs heavily against his optimism. In other words, one of the things that annoys me about the way Enneagram experts talk about people is the incessant stereotyping. For instance, Beck says something about himself, and Cron responds, “Sure, because 5s. . . . ” But when Beck doesn’t fit the 5, it’s Beck’s “4 wing” causing the exception. In effect, this means you should recognize yourself in a number, unless you don’t, in which case another number explains the discrepancy, but we’ll still refer to your number. At the end of the day, the generalization of the Enneagram has very limited explanatory power, and Cron knows it. But when he talks about the problem of stereotyping he says the Enneagram is, “wrong, but it’s useful. . . . It’s true enough.” But is it? True enough for what? We return to the pragmatic question. What is the Enneagram doing, or what do people think it’s doing?

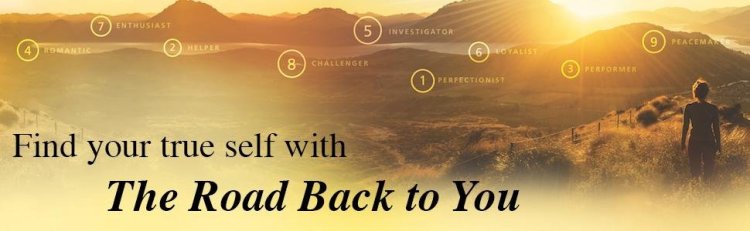

The apparent answer to that question is where my fundamental concern arises, and (surprise!) it is a theological concern. The title of Cron’s book goes a long way toward putting the problem into words: The Road Back to You: An Enneagram Journey to Self-Discovery. Speaking for myself, I’m confident that taking the road back to me is a terrible idea. Speaking generally from a theological standpoint, why would a Christian think that sounds like a good idea? How about, instead, the road back to God: a journey of dying to self?

I am asking this question as someone whose research is, in large part, focused on the human self, so I can’t be taken to dismiss the importance of the topic offhandedly. But a primary reason the topic is important is because of the malformation of the self in postmodern Western culture—a malformation due in large part to self-obsession. In my view, the constitution of the self outside or beyond the self, in the other, and ultimately in the Holy Other, is the great concern. But the contemporary Enneagram fad seems to be playing right into the self-centeredness of the selfie world. And, I have to say, brazenly so. Consider the marketing on the Amazon page for The Road Back to You:

I mean, really? My true self? By focusing on myself? I’m forced to make the counter claim: my true self is not to be found by turning back into myself, something theologians call homo incurvatus in se (the human turned in on him/herself). Rather, the true self is constituted and found extra se, in Christo (outside oneself, in Christ). I have a boatload to say about this idea, but there’s the barebones claim. It is a conviction that makes my gut clench when I hear the rhetoric in which the popular use of the Enneagram is steeped, which sounds very like spiritual self-helpism.

This concern has everything to do with Cron and Beck’s discussion of character and personality. As a matter of spiritual growth (character development), I’m an advocate of both self-awareness and spiritual direction. To the extent that the Enneagram was developed and is used for spiritual direction that leads to self-awareness, I’m interested and open. And I suspect that much of what is happening in the positive experience of the Enneagram is not that it provides uniquely true insight but that, more basically, it is a tool that provides a missing opportunity for self-assessment and spiritual growth, especially among those who are not being discipled actively or spiritually directed. And much of the time, the valuable result is not the revelation that I’m this number or she’s that number but rather the fact that I’m actually taking the time to reflect on my sin in relation to her.

Basically, we need to grow up, bear spiritual fruit, develop character. Whether I “know my number” is of relatively little importance. Which is why I love it when Beck says (starting about 33:50): “A lot of those descriptions of just kind of a straight 5 maybe doesn’t seem to fit me if somebody’s looking at it from the outside in because I seem so relational and involved in my church. But all of that to say those social things that people observe about me are probably not natural, like, they were acquired intentional disciplines, because I felt like the way of Jesus was calling me into those practices.” Yes! It’s not his “4 wing” that explains why the stereotype fails. It fails because he’s a disciple of Jesus who has grown beyond himself in Christ. The way (road!) of Jesus is calling us to that kind of self-awareness, growth beyond ourselves, and, indeed, death to self. If the Enneagram serves that end, great. If it serves to lead you back to yourself, run the other direction.

In the context of my research, I find myself wondering what makes the Enneagram so fascinating among my American friends today. To refer back to Beck’s point, why does it work so well? If your inclination is to say it works because it’s true—because it is somehow universal—then you need a reality check. Yes, it does really work for a lot of people in the US (the West?) right now. It is actually intuitive and helpful. But intuition is contextual, and the help it provides makes a difference for a socially determined problem, namely, the postmodern disintegration of the self and the generalized identity crisis of a people turned desperately in on themselves. In this context, the Enneagram seems to have teeth, and although the marketing of The Road Back to You betrays why that is generally, I think there are still good questions to ask about what makes this model of self-reflection incisive specifically.

So, my position is not final. This is the beginning of a conversation, and I’m “open.” But that’s about the most I can say.

I’ll end on a light note from another friend who appreciated Cron’s book. He (who will remain anonymous unless he wants to own his genius in the comments) said, “The Enneagram is like your blood pressure. It’s probably a good idea to know your number, but no one wants to hear you talk about it.”

Let that be a reminder to the Enneagram enthusiasts.