Worldview

I hope to pursue doctoral research in missional hermeneutics, focusing among other things on a missiological conception of worldview. I emphasize a missiological conception, because that qualification signals a very specific appropriation of a problematic concept. In a recent exchange with a New Testament scholar about my research interests, he stated:

I do wonder whether “world view” studies is the direction to go. This way of construing things has been roundly critiqued for its overly philosophical orientation, and the priority it seems to give to one’s explicit commitments. From a missiological perspective, you may want to work more from the perspective of “culture” anyway, and perhaps from the standpoint of a religious studies orientation. (Of course, you may already be using the language of “world view” in a more chastened way, taking into account already the criticisms leveled against this term.

It was necessary to clarify that, as a missiologist, I view worldview differently than some of its contested philosophical formulations. (By the way, having clarified my slant, my conversation partner was more positive, though still cautious.)

I cut my worldview teeth on Paul Hiebert’s work, which is to say, on missionary anthropology, which is patently cultural and, certainly in Hiebert’s case, chastened. But philosophical conceptions of worldview and related concepts—which are very difficult to distinguish in the mishmash of philosophers’ works—have also undergone a rather radical transformation. While a philosophical conception of worldview can’t help being overtly philosophical (though perhaps “abstract” is really the problem in view), the shift in philosophy has been away from the priority of explicit commitments. If it weren’t for this evolution in philosophy, in fact, the missiological conception wouldn’t have much clout, since it would be misappropriating an established term. On the contrary, the historical development of the analytical construct indicates that the meaning of worldview is still contested—which the turn toward the tacit nature of worldview has ironically exacerbated. Scott Moreau has recently written:

There are formidable challenges to using the broad construct of “worldview” as a significant tool in contextualization. One is that the very hiddenness of worldview makes it extraordinarily difficult—perhaps impossible—to grasp well enough to use as an analytic tool. We may instinctively resonate with its viability, but once we try to articulate concretely what comprises “worldview,” we discover it to be impossible. . . .

Despite the challenges, Hiebert postulates, “If behavioral change was the focus of the mission movement in the nineteenth century, and changed beliefs its focus in the twentieth century, then transforming worldview must be its central task in the twenty-first century.” [emphasis Moreau’s] . . . Even though we have no coherent consensus on how to understand it, engage it, or transform it, it seems clear that the concept of worldview will continue to serve as a foundational and guiding idea for innumerable evangelical efforts. (Moreau, 148–49)

Perhaps the accent to should lie on mission and evangelical, though, because many secular anthropologists also see worldview as a marginal. David Beine was provoked by a “lively anthropology listserve discussion” to investigate whether the comments on worldview there were indicative of American anthropology. Comments such as, “Worldview, however, is now so particular to the missiological community, that I wonder why it should be defended,” mark the distinction between secular and missiological anthropology clearly enough (Beine, 5). But Beine’s preliminary findings suggest that worldview is still a fruitful analytical construct in a number of anthropological subspecialties, taught in many universities throughout the US. He wonders whether it has not, in other subspecialties, simply been eclipsed by other concerns rather than really rejected (Beine, 4).

In any event, I am supposing the further development of worldview as the basis for the theological rapprochement I’ve discussed so far in this series and, by extension, as an integral part of the missional hermeneutics proposal I hope to elaborate. To clarify, I will present a provisional understanding of worldview.

Worldview in Missiological Anthropology

I begin with a couple of anthropologically oriented models, which establish from the outset that I am working first from the perspective of “culture” and only subsequently from philosophy, though the two will not be separate in the end. First, Charles Kraft’s Christianity in Culture (1979; 2nd ed. 2005) has been an influential textbook. To begin with, Kraft defines culture as:

A label for the nonbiological, nonevironmental reality in which humans live. Here we postulate a view of reality that sees certain phenomena as best explained in terms of this mental construct. We also advance a particular understanding of that mental construct as labeling only structure, never people. That is, I here attempt both to look at reality via the cultural model and to develop a model of culture itself. In the conceptualization of culture here assumed, there are certain closely related submodels that are crucial to the understanding toward which I seek to lead the reader. (Kraft, 2005, 37–38; emphasis added)

I highlight two points. One, as a model by which to understand reality, culture and its submodel worldview are themselves part of a worldview. More accurately, the worldview model is a kind of meta-view of reality—a view of the way people view reality. This is a point that inevitably arises in the discussion of worldview, particularly the history of its conceptualization and the critique of its ultimate value. At this point I simply acknowledge the fact and accept it; the use of worldview is a part of my worldview. It is a commitment I own and the ground from which I chose (insofar as it’s a choice) to develop a hermeneutics. Out with naiveté; in with provisional, self-critical commitment. Two, worldview is a submodel of culture. It is not separate from but rather internal to and continuous with culture. Thus:

A worldview is seen as lying at the heart of every cultural entity (whether a culture, subculture, academic discipline, social class, religious, political, or economic organization, or any similar grouping with a distinct value system). The worldview of a cultural entity is seen as both the repository and the patterning in terms of which people generate the conceptual models through which they perceive of and interact with reality. (Kraft, 2005, 43; emphasis added)

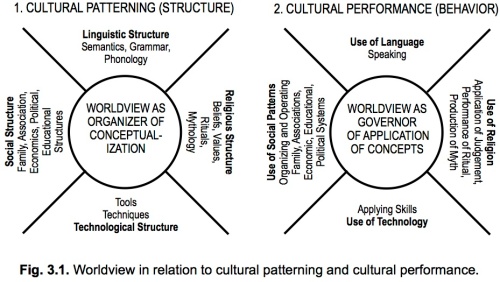

The worldview serves two essential functions: an “organizing” function in relation to a culture’s conceptualizations and a “governing” function in relation to those conceptualizations’ applications:

Kraft conceives of five “major functions” of worldview:

(1) Explanatory: “to codify the society’s explanations of how and why things got to be as they are and how and why the continue or change;” to embody “for a people, whether explicitly or implicitly, the basic assumptions concerning ultimate things on which they base their lives” (Kraft, 2005, 44).

(2) Evaluational: to serve “an evaluative—judging and validating—function;” to provide “guidelines in terms of which evaluations are made” (Kraft, 2005, 45).

(3) Reinforcing: to provide “psychological reinforcement,” especially manifest in ritual, ceremony, or observances, thus providing “security and support for the behavior of the group in a world that appears to be filled with capricious uncontrollable forces” (Kraft, 2005, 45).

(4) Integrating: to serve “an integrating function” as an ordering of “their perceptions of REALITY into an overall design,” thereby in combination with explanatory, evaluational, and reinforcing functions becoming “a system of symbols that acts to establish powerful, pervasive, and long-lasting moods and motivations in people by formulating conceptions of a general order of existence and clothing these with such an aura of factuality that the moods and motivations seem uniquely realistic” (Kraft, 2005, 46).

(5) Adaptational: to serve an “adaptational” function, “resolving conflict and reducing cultural dissonance . . . in circumstances of cultural distortion or disequilibrium” (Kraft, 2005, 46).

Kraft subsequently elaborates worldview somewhat differently in Anthropology for Christian Witness (1996). There he defines worldview as “the culturally structured assumptions, values, and commitments/allegiances underlying a people’s perception of reality and their responses to those perceptions” (Kraft, 1996, locs. 1548-1549). He discusses five characteristics and fourteen functions of worldview. The characteristics of worldview are (Kraft, 1996, locs. 1625–1687):

(1) Its “assumptions and premises are not reasoned out” but “seem absolute and are seldom questioned”

(2) It provides people with “a lens, model, or map in terms of which REALITY is perceived and interpreted”

(3) It organizes a people’s “life and experiences into an explanatory whole that it seldom (if ever) questions unless some of its assumptions are challenged by experiences that the people cannot interpret from within that framework”

(4) It causes the differences between cultures that are “most difficult to deal with”

(5) “Though we need to treat people and cultural/worldview structuring as separable entities, in real life, people and worldview function together”

In this assumptive, mediatory, integrative, renitent mode, worldviews function to “pattern” human culture (Kraft, 1996, locs. 1698– 1828):

On the primary level of “structuring deep, underlying personal characteristics,” worldviews “pattern”:

(1) Will—ways of making decisions, e.g., individualistically vs. collectivistically

(2) Emotions—use of expression, e.g., publicly vs. privately

(3) Logic and reason—varieties of logic, e.g., linear vs. contextual

(4) Motivation—socially inculcated desires, e.g., prestige, wealth, comfort, freedom

(5) Predispositions—attitudes or outlooks, e.g., optimism vs. pessimism

On the subsequent level of “the assignment of meaning,” worldviews “pattern”:

(6) Interpreting—social agreements about the meaning of cultural forms, e.g., beautify vs. ugly

(7) Evaluating—”feelings” about interpreted meanings, e.g., good vs. bad or right vs. wrong

Finally, on the level of “how people respond to the meanings they assign,” worldviews “pattern”:

(8) Explaining—assumptions concerning the way things are or should be, e.g., the nature of humans

(9) Pledging allegiance—differentiation and prioritization of commitments, e.g., job vs. family

(10) Relating—ways of relating, e.g., competition vs. cooperation or hierarchy vs. equality

(11) Adapting—coping mechanisms, e.g., denial vs. change or fight vs. flight

(12) Regulating—guidelines for steering behavior, e.g., incarceration vs. death or shame vs. guilt

(13) Getting psychological reinforcement—assumptions about what to do in crises or transitions, e.g., ceremonies and rites

(14) Integrating and attaining consistency in life and the way it is structured—application of the same principles and values in all areas of life, e.g., egalitarianism at work affecting male dominance at church

It is clear that Kraft as parsed out his original “major functions” in more detailed fashion, which is beneficial. Yet, for me his explanation has a certain conceptual ambiguity working against it (possibly because I’m helped by visualization). For a more concise model, into which Kraft’s insight can be worked, I turn to Paul Hiebert’s work.

Hiebert’s introductory discussion of worldview in Anthropological Insights for Missionaries (1985), which extends his earlier discussion in Cultural Anthropology (1976), defines culture as “the more or less integrated system of ideas, feelings, and values and their associated patterns of behavior and products shared by a group of people who organize and regulate what they think, feel, and do” (Hiebert, 1985, 30). And like Kraft, he understands worldview as an underlying aspect of culture. He defines it simply as “the basic assumptions about reality which lie behind the beliefs and behavior of a culture.” Having described culture in terms of three dimensions—cognitive (knowledge, logic and wisdom), affective (feelings, aesthetics), and evaluative (values, allegiances)—Hiebert specifies that each cultural dimension has corresponding assumptions (Hiebert, 1985, 45–47):

(1) Cognitive or existential assumptions “provide people with the fundamental cognitive structures people use to explain reality,” “furnish people with their concepts of time, space, and other worlds,” and “shape the mental categories people use for thinking” such as “kinds of authority” and “types of logic.” “Taken together these assumptions give order and meaning to life and reality.”

(2) Affective assumptions “underlie the notions of beauty, style, and aesthetic” and “influence . . . tastes in music, art, dress, food, and architecture as well as they ways they feel towards each other and about life in general.”

(3) Evaluative assumptions “provide the standards people use to make judgements, including their criteria for determining truth and error, likes and dislikes, and right and wrong” and “determine the priorities of a culture and thereby shape the desires and allegiances of the people.”

Hiebert’s model of worldview, which is an iteration of the well-known “culture onion,” initially looks like this:

The model is instructive. First, it makes an interesting statement about the relationship of the dimensions: the affective being more interior than the cognitive and the evaluative more interior than the affective. There is a difficulty in representing the dimensions’ relationship to each other here. Is the evaluative more fundamental or essential? Are all dimensions always equally operative or influential? Kraft’s notion of “sociocultural specialization” might be applied (somewhat differently than he intends; Kraft, 1996, loc. 1584) to indicate how cultures may emphasize one dimension more than another. Anyhow, the model also indicates clearly the rootedness of “explicit beliefs and value systems” in the implicit dimensions of worldview. The listing of specific cultural systems in the outer ring is helpful, but it also visually obscures the sense of each dimension having an explicit expression or, from the other direction, of each system featuring both implicit and explicit components of each dimension. For example, religion has implicit and explicit components of the cognitive, affective, and evaluative dimensions. Also missing is the sense in which, once explicit, the systems have become cultural manifestations as products, behaviors, and symbols (Hiebert, 1985, 35–37):

Taken together, cognitive, affective, and evaluative assumptions provide people with a way of looking at the world that makes sense out of it, that gives them a feeling of being at home, and that reassures them that they are right. This world view serves as the foundation on which they construct their explicit belief and value systems, and the social institutions within which they live their daily lives. (Hiebert, 1985, 47–48)

Hiebert, like Kraft, lists some functions of worldview (Hiebert, 1985, 48):

(1) It “provides us with cognitive foundations on which to build our systems of explanation, supplying rational justification for belief in these systems”—”provides us with a model or map of reality by structuring our perceptions of reality”

(2) It “gives us emotional security”—”buttresses our fundamental beliefs with emotional reinforcements so that they are not easily destroyed”

(3) It “validates our deepest cultural norms, which we use to evaluate our experiences and choose courses of action”—”provides us with a map of reality and also serves as a map for guiding our lives”

(4) It “integrates our culture”—”organizes our ideas, feelings, and values into a single overall design”

(5) It (following Kraft explicitly) “monitors cultural change”—”to select [ideas, behaviors, and products] that fit our culture and reject those that do not,” “to reinterpret those we adopt so that they fit our overall cultural pattern.”

These five functions seem to parallel Kraft’s early five functions directly; there is significant agreement here. Hiebert’s construal makes an important clarification: the cognitive, affective, and evaluative dimensions all together are what worldview comprises, and it is worldview as a whole that provides these functions. Thus while the explanatory and evaluational functions (to adopt Kraft’s terms) seem to reprise Hiebert’s cognitive and evaluative dimensions, we may infer that the unified worldview is active in all five functions. Hiebert’s thinking develops into Transforming Worldviews, published posthumously in 2008. The initial chapters sprawl, causing the reader (or me, at least) to experience the complexity and multifaceted texture of their subject matter.

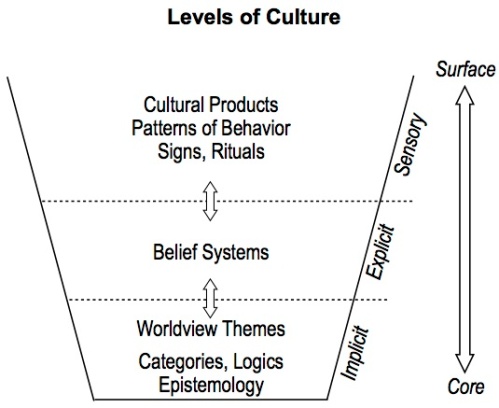

Chapter one surveys the anthropological heritage of worldview, introducing thereby some key concepts that Hiebert will take up. In the mean time, he sets out a “preliminary definition” of worldview: “the foundational cognitive, affective, and evaluative assumptions and frameworks a group of people makes about the nature of reality which they use to order their lives” (Hiebert, 2008, 25–26). He now represents worldview graphically within a model of culture:

The relationship between the three dimensions has been reconfigured. All three are now seen as equal components, and the dimensions of worldview are now clearly a subset of the dimensions of culture. The dotted lines are important; they indicate that the dimensions are distinguished “for analytical purposes” rather than being truly separate, and they indicate that the line between worldview and the rest of culture is porous or, as Hiebert might say, fuzzy. The inner worldview triangle might be taken to mark off the implicit from the explicit, but that would make worldview fully implicit (the fuzziness of the line notwithstanding), which is not the case. Also, the linear rendering of decisions, behaviors, and products loses the earlier model’s representation of continuity and reciprocity between worldview and social institutions (bidirectional arrows from inside to outside) as well as the various social institutions’ systemic integration (bidirectional arrows around the outer circle). Still, Hiebert has much more to say about worldview than the graphic captures.

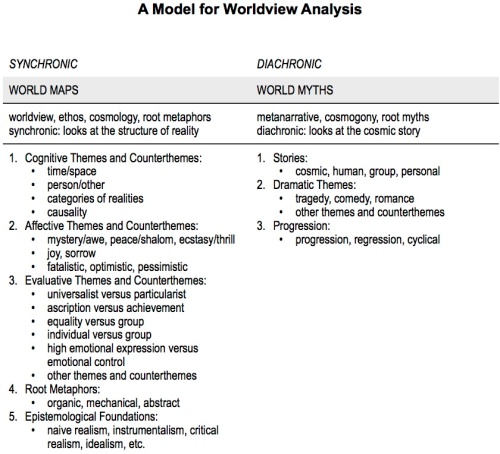

He conceives of worldview both synchronically and diachronically. Synchronically, he adopts Morris Opler’s notion of themes and counterthemes, to which he adapts Robert Redfield’s universal cognitive categories: time, space, self and others, nonhumans, causality, and common human experience. Additionally he looks for themes and counterthemes emically identified in one culture to compare with another culture. Themes allow one to see “how people view the structure of the world.” But it is necessary to supplement “a diachronic dimension to see how people look at the human story” (Hiebert, 2008, 26–28).

Interestingly, Hiebert recapitulates the functions of worldview in much the same terms but splits “emotional security” and “psychological reassurance” into separate functions, resulting in six functions. Psychological reassurance in this usage seems to be simply an extension of the adaptational function. The original five seem sufficient to me.

The second chapter of Transforming Worldviews deals with the characteristics of worldview, which are best viewed in outline form in order to capture the gist of his analysis. I’m going to create a patchwork of Hiebert’s words and ideas in the outline, quoting him more directly at some times than others, along with my own comments:

I. Synchronic Structures

A. Depth: worldviews underlie the more explicit aspects of culture. Below products, behavior, and speech are myths and rituals that define and establish themes. Below myths and rituals are systems of beliefs that encode cultural knowledge. Below systems of beliefs are unseen structures underlying the entire explicit culture—the worldview. There is an important connection here with both linguistics and psychology. Depth does not equate to foundationalism, because causality goes both ways. Surface culture can transform worldview (Hiebert, 2008, 32). Hiebert depicts depth with this graphic:

1. Category Formation:

a. Digital and Analogical Sets: the way people form mental categories. Digital sets are well formed or clearly defined with a finite number of categories in a domain. Associations include the classical laws of thought (Identity, Non-contradiction, Excluded Middle), propositional logic (discussed below), Euclidean geometry, and Cantorian algebra. Analogical sets are “fuzzy” and have an infinite number of steps between in and out and between one set and another. All cultures use both well-formed and fuzzy sets. The difference lies in which is more fundamental to the thinking of the people.

b. Intrinsic and Relational Sets: what defines a set. Intrinsic sets are defined by intrinsic characteristics—what a thing is. Extrinsic sets are relational—defined by what a thing is related to.

c. Folk and Formal Taxonomies: Folk taxonomies are high-context and concretely functional in regard to culturally significant properties, such as edible and non-edible nuts. Formal taxonomies are low-context and highly abstract in regard to the underlying nature of reality. [Hiebert’s description of category formation is a formal taxonomy.]

2. Signs: the relationship between categories and reality. One view is that signs point to objective realities. Another view is that signs are constructs that shape the way people see reality, evoking subjective images in the mind. Another view is that signs both point to external realities and evoke subjectives images in the mind. Kinds of signs include discursive language; symbols, whose meaning can be iconic or assigned; performative language; and parametric signs, which point beyond their content.

3. Logics: (note how these are derivative of kinds of category formation)

a. Abstract Algorithmic Logic: propositional or digital logic. It is abstract because it creates concepts in which the relevant features of certain prototype phenomena have been abstracted from the irrelevant features. It uses such concepts as units of analysis to reason reductively (in terms of binary oppositions) and mechanistically or formulaically (in terms of necessary outcomes).

b. Analogical Logic: “fuzzy logic.” Not less precise than algorithmic logical but more precise, it is based on analogical or ratio sets that have an infinite number of points between zero and one and between one and two, therefore dealing with higher levels of complexity.

c. Topological Logic: also called analogical logic, with a different meaning than the above type. Complex realities are examined by comparison with known realities, thus by analogy. Modern law, reasoning from case to case on the basis of similarities, is analogical. The root metaphors (Stephen Pepper) of a worldview are related to this kind of logic. Hiebert finds organic and mechanistic to be culturally universal root metaphors, which lead to two kinds of knowledge: interpersonal and impersonal.

d. Relational Logic: concrete functional logic. See informal taxonomies above. [I find this section to be redundant, by the way.] It it is ironically difficult to describe concrete functional logic abstractly. So Hiebert works with taxonomic examples, hence the redundancy with category formation. The difficulty is describing the nature of the reasoning process per se; it is easier to demonstrate its conclusions. It is critical to see logic and reason here in terms of their function in life. Whereas most modern people will say a log does not belong with an axe, a hammer, and a saw, because it is reasonable to classify the latter three as tools, other people will say it is far more reasonable to group the axe and the hammer with the log, in order to build something. The modern mind immediately objects that the point of the exercise is to categorize, not to build. And here is where the force of relational logic comes to light. Someone who sees the world primarily through relational logic naturally reasons about everything in more concrete, functional terms. The request to categorize objects abstractly cannot overrule the operative logic, which is not less logical for being intransigently functional. This peels back another layer, raising the question of how one determines what is functional. Modern cultures have got a tremendous amount of function out of reasoning abstractly. Functionality depends on perceived need, though, and the fact that perception is what worldview is about indicates the systemic nature of worldview and therefore the unbelievable difficulty of discussing one characteristic of worldview apart from all the others, that is, abstractly!

e. Wisdom: evaluative logic. Assessments are based on the knowledge at hand, the factors involved, and a comparison with previous experiences, rather than by a formula that produces the right results. (I can’t resist pointing out that Hiebert’s example contrast between algorithmic and evaluative logic is a question about the best way to get from one place to another, asserting the the wise cabby will take into account the time of day, weather, construction, and accidents. I’m afraid Google Maps is part of a monstrous algorithm machine that takes all of those “wisdom” factors into account. It can be, actually, very wise to use an algorithm. I’m not arguing against the value of wisdom as Hiebert sees it; just saying.)

4. Causality: a “toolbox” of different belief systems a culture uses to explain what is happening. These tools function ad hoc: ordinary people are more concerned about healing and success than ultimate causality, often using serval different explanation systems and treatments at the same time, most of which reside at the folk level, hoping that one of them will work. Formal explanations (e.g., theodicy) are often a last resort.

5. Themes and Counterthemes: Opler defines a cultural theme as “a postulate or position, declared or implied, usually controlling behavior or stimulating activity, which is tacitly approved or openly promoted in a society.” Hiebert conceives of root metaphors as basically synonymous with themes.

6. Epistemological Assumptions: assumptions a culture makes about the nature of reality and human knowledge. Especially given the vagueness of this definition, Hiebert’s single paragraph on epistemology is reductive, but he does have a whole book on the subject (Missiological Implications of Epistemological Shifts).

B. Implicit: As the definition of depth above already asserts, worldviews are mostly unexamined and implicit. And various points have already indicated that worldview is itself a “fuzzy set.” The relationship between what is explicit or implicit, overt or covert, express or tacit, asserted or presuppositional, theoretical or pretheoretical is organic, not binary. On one hand, “it is this implicit nature of worldviews that makes it so hard to examine them. They are what we use to think with, not what we think about.” On the other hand, “worldviews can also be made visible by consciously examining what lies below the surface of ordinary thought.” It is obviously a dilemma to think about what we think with, but that is exactly what Hiebert (for example) is doing, and if we can note how his worldview is operative in the process, that does not invalidate the findings (lest we engage in a cum hoc ergo propter hoc fallacy—yes, I’m using propositional logic!). But once we’ve granted that we can explicate at least some of the implicit, what is explicated does not cease to be part of worldview. Therefore, without making a programatic claim about our ability to be absolutely reflexive, it is fair to say that implicitness is not an essential characteristic of worldview, but worldview is, for practical purposes, always more implicit than explicit.

C. Constructed and Contested: “Knowledge systems involve a process of reflection entailing a reorganization of thought. This reorganization that occurs through the application of mental processes (such as category formation and logic), the formation of alternative models, and the selection of certain models over others after evaluation. Over time the systems become progressively more adequate. In short, culture is not the mere sum of sense data. It is comprised of the gestalts, or configuration of sense data plus memory, concept formation, verbal and other symbolic elements, conditioned behavior, and many other factors.” Subalterns also contest the worldviews of power holders, which tension provokes constant change.

D. More or Less Integrated Systems: “Worldviews are paradigmatic in nature and demonstrate internal logical and structural regularities that persist over long periods of time. . . . The configurational nature of worldview gives meaning to uninterpreted experiences by seeing the order or the story behind them.”

E. Generativity: Worldviews are not the specific instances of human speech and behavior but rather generate speech and behavior. Hiebert cites the rules of chess and the rules of a language as examples of generativity, concluding that “worldviews are the elements or rules of a culture that generate cultural behavior.” He does not make any reference to Ludwig Wittgenstein in this regard, a connection whose importance I will make clear later.

F. Dimensions of Worldview

1. Cognitive Themes: Despite dealing with categories and logic under “depth,” Hiebert notes that they belong in the cognitive dimension. (This is, in my opinion, a major organization flaw in the book.) Beyond these, he deals with with the themes and root metaphors mentioned many times heretofore.

a. Time

b. Space

c. Organic/Mechanistic

d. Individual/Group

e. Group/Others

f. This World/Other Worlds

g. Other Themes: Culturally particular themes emically determined.

2. Affective Themes: Hiebert adds little to the short description in his earlier work, but he does provide an interesting taxonomy of affective types in American Protestant worship services, which links differences in mood to differences in architecture, posture, theological focus, central message, and central story. It is not clear, however, how one might get a handle on affective “themes” on par with cognitive themes.

3. Evaluative Themes: normative assumptions, such as virtues, standards, morals, and manners, though presumably the accent should be on the implicit aspects norming the typically explicit “assumptions” he mentions.

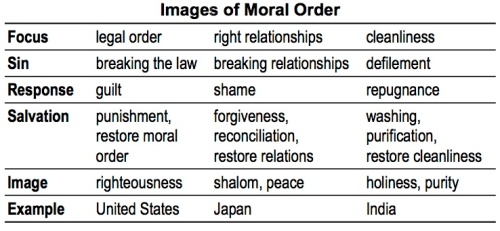

a. Moral Order: Worldviews differ according to what are perhaps best described as moral “centers”: relationship, law, and purity. Hiebert’s diagram explains the distinctions:

I would add that the center amounts to an emphasis. For example, it seems to me that the interrelation of righteousness, peace, and holiness in the Hebrew worldview makes for a composite center: purity laws affect relationships.

b. Heroes and Villains: This passage bizarrely says nothing about heroes and villains. The closest Hiebert comes is to say that “evaluative standards determine in each society what an ideal man and woman looks like, what constitutes a good marriage, and how people should relate to one another and to strangers. At the deepest level, evaluative assumptions determine fundamental allegiances—the gods people worship, the goals for which the live.” I have to say, this looks backwards. For one thing, archetypal figures—Heroes and Villains—are arguably more determinative of evaluative standards than determined by them. I would connect this with the narrative dimension of the diachronic characteristics of worldview below. For another, fundamental allegiances are arguably more determinative of evaluative assumptions than determined by them. Both of these observations would seem to be more in line with the section’s thrust: to explain what composes and influences the evaluative dimension, rather than to discuss what the evaluative dimension generates.

c. Parsons’s Evaluative Themes: These are similar to Redford’s themes in that they are assumed to be universal. They are similar to Opler’s in that they are polar: emotional expression vs. emotional control; group centered vs. individual centered; other-world orientated vs. this-world oriented; emphasize ascription vs. emphasize achievement; focus on whole picture vs. look a specific details; universalist vs. particularist; hierarch is right vs. equality is right. These evaluative norms are “values” in Hiebert’s discussion of Parsons. This might be obvious given the semantic correlation, but we are trying to get our minds around what generates values, not what our values are per se. Here again the organic continuity between implicit and explicit is a factor. And we are not talking about merely what I value without “living the examined life” but what, in terms of depth, generates and regulates the formation and revision of our explicit values. It is interesting to compare Parsons’s evaluative list with the cognitive themes listed earlier. There is some overlap, and certainly some of the cognitive themes are value-generating as well (to reiterate, the three dimensions of worldview are divided heuristically, not hermetically; they function as a whole). Likewise, emotional expression vs. emotional control would likely be discussed best under the affective dimension. A comparison with Sherwood Lingenfelter and Marvin Mayers’s “model of basic values” is indicative of the problem (Ministering Cross-Culturally, 2nd ed. 2003). Their analysis serves to uncover implicit values. Though these values are an implicit aspect of culture much of the time, they are not the stuff of the evaluative dimension of worldview but rather manifestations of worldview. A couple of the typical cultural onion models should clarify somewhat. First, one of the most well-known is Geert Hofestede’s:

There are clear echoes of this model in Hiebert’s discussion of Heroes and Villains. And as in the discussion of Parsons, “values” are the core element (“core values” is the popular terminology). Of course, worldview does not figure in this idea of culture, and it is important to locate Hofstede’s even more well-known dimensions of culture (http://geert-hofstede.com/dimensions.html) within this model. Hofstede’s definition of values is: “broad tendencies to prefer certain states of affairs over others,” which deal with pairings such as evil vs. good, dirty vs. clean, dangerous vs. safe, forbidden vs. permitted, decent vs. indecent, moral vs. immoral, ugly vs. beautiful, unnatural vs. natural, abnormal vs. normal, paradoxical vs. logical, and irrational vs. rational (Hofstede, Hofstede, and Minkov, 8–9). A dimension, on the other hand, is “an aspect of culture that can be measured relative to other cultures . . . [that] groups together a number of phenomena in a society that were empirically found to occur in combination” (Hofstede, Hofstede, and Minkov, 31). Though the analytical emphasis is necessarily on the empirical, the purpose of grouping cultural phenomena into an abstract category is to identify an underlying (i.e., implicit) disposition or construct. As in his model of culture, the practices he empirically examines are rooted in values, and although his dimensions are not listed in his example value polarities, they are identical in both polar structure and function: “power distance (from small to large), collectivism versus individualism, femininity versus masculinity, and uncertainty avoidance (from weak to strong)” (Hofstede, Hofstede, and Minkov, 31). This is why the analysis of Hofstede’s dimensions of culture looks very similar to the analysis of Lingenfelter and Mayers’s basic values. Likewise, “Trompenaars and Hampden-Turner identify seven value orientations. Some of these value orientations can be regarded as nearly identical to Hofstede’s dimensions” (Dahl, 2004, 14). Fons Trompenaars and Charles Hampden-Turner’s model of culture is for my purposes an improvement upon Hofstede’s, as it comes closer to a conception of worldview:

Tellingly, norms and values here are somewhere between the implicit and explicit levels. Though an improvement, the model still might be more complete. Concordia University – Saint Paul professor Eugene Bunkowske’s model (http://web.csp.edu/MACO/Courses/573/Microsoft_Word_-_Oni.pdf) represents an attempt from a Christian missiological perspective to conceive of the cultural onion comprehensively. Here is a composite I created of his conception:

Bunkowske’s model in my view does three things correctly relevant to this aside on Hiebert’s discussion of the evaluative dimension. One, he places ultimate allegiance at the core of worldview rather than making it a consequence of worldview’s evaluative dimension. Two, he places “values” on a more outlying level than worldview (so Trompenaars and Hampden-Turner). Three, he describes the level of beliefs-values-feelings as “evaluative,” reflecting the way (in my reading) Hiebert’s three dimensions work together (a) to regulate the implicit evaluative process and (b) to produce explicit values. That’s enough for the aside. In short, these are points I will take into consideration as I attempt to compose a model of worldview.

G. Three Dimensions: “Together, cognitive, affective, and evaluative assumptions provide people with a way of looking at the world that makes sense out of it, that gives them a feeling of being at home, and that reassures them that they are right. This worldview serves as the deep structure on which they construct their explicit belief and value systems and the social institutions in which they live their daily lives.”

II. Diachronic Characteristics: By comparison, the discussion of worldview’s diachronic characteristics is minimal. This is the greatest problem with Hiebert’s conception. Yet, his construal of the diachronic aspect as “narrative knowing” is right: “At the core of worldviews are foundational, or root, myths, stories that shape the way we see and interpret our lives” (Hiebert, 2008, 66; emphasis added). This is myth in the technical sense:

A myth is the overarching story, bigger than history and believed to be true, that serves as a paradigm for people to understand the larger stories in which ordinary lives are embedded. Myths are paradigmatic stories, master narratives that bring cosmic order, coherence, and sense to the seemingly senseless experiences, emotions, ideas, and judgements of everyday life by telling people what is real, eternal, and enduring. (Hiebert, 2008, 66)

This critical insight needs to be expanded programatically. Nonetheless, Hiebert’s intention, in the end, is to create a model for worldview analysis that takes into account both synchronic and diachronic aspects of worldview:

Thus we have a strong theoretical foundation from the missiological anthropology side, as well as a number of questions and weaknesses. In conversation with philosophical analysis of worldview, it will be possible to construct an even richer model of worldview.

Cited

Beine, David. “The End of Worldview in Anthropology?” SIL Electronic Working Papers 2010-004 (September 2010): 1–10, http://www-01.sil.org/silewp/2010/silewp2010-004.pdf.

Bunkowske, Eugene W. “The Cultural Onion.” http://web.csp.edu/MACO/Courses/573/Microsoft_Word_-_Oni.pdf.

Dahl, Stephan. “Intercultural Research: The Current State of Knowledge.” Middlesex University Business School Discussion Paper 26 (January 2004): 1–21.

Hiebert, Paul G. Anthropological Insights for Missionaries. Grand Rapids: Baker, 1985.

________. Transforming Worldviews: An Anthropological Understanding of How People Change. Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2008.

Hofstede, Geert, Gert Jan Hofstede, and Michael Minkov. Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind. 3rd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2010.

Kraft, Charles H. Anthropology for Christian Witness. Kindle ed. Maryknoll, NY: Orbis, 1996.

________. Christianity in Culture: A Study in Biblical Theologizing in Cross-Cultural Perspective. 25th Anniversary 2nd ed. Maryknoll, NY: Orbis, 2005.

Lingenfelter, Sherwood G., and Marvin K. Mayers. Ministering Cross-Culturally: An Incarnational Model of Personal Relationships. 2nd ed. Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2003.

Moreau, A. Scott. Contextualization in World Missions: Mapping and Assessing Evangelical Models. Grand Rapids: Kregel Academic 2012.

Trompenaars, Fons, and Charles Hampden-Turner. Riding the Waves of Culture: Understanding Cultural Diversity in Business. Santa Rosa, CA: Nicholas Brealey, 1998.

Hi Greg, thanks for your helpful summary and reflections on worldviews. I’m doing a research paper on cultural anthropology for Christian mission and would love to read up on Bunkowske’s model. The link provided doesn’t seem to be working anymore – would it be possible for you to give me the citation details of the original article please? Many thanks, Joy

LikeLike